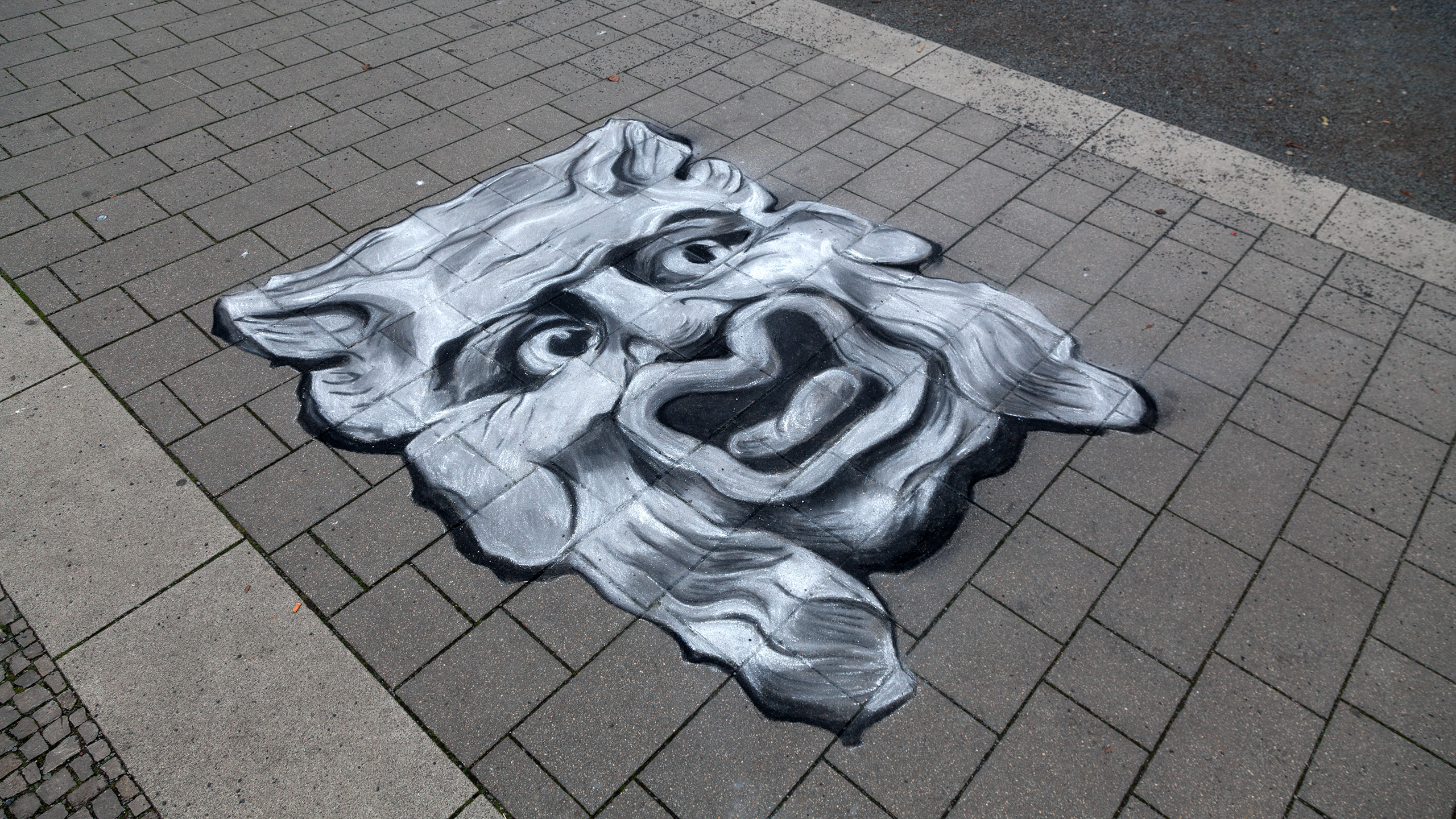

Leopoldplatz is currently being transformed into a friendlier and safer place. Art plays a role in this process, and cultural events aim to make the square more attractive and accessible. The work addresses this gentrification process by focusing on the role of art in the creation of the neighbourhood around Leopoldplatz in the 19th century. The drawings show so-called “apotropaic ornaments” or guardian spirits, mythical creatures, often hybrids of humans, plants and animals, which can be found on house facades surrounding Leopoldplatz. Their grotesque expressions mirror the often rough, pale and lethargic facial expressions of the drug users in the area. Originally, these ornaments were intended to ward off evil spirits so that they could not enter the building.

During Berlin’s rapid growth in the 19th century, almost all houses were built with this type of decoration. With their lavish decorations, many builders focused more on appearance than quality in order to drive up the price of the houses. The war, but also a change in cultural perception due to new modernist ideals, caused many of the decorations to disappear. The modernists criticised the use of ornamentation as merely a beautiful appearance that concealed the often harsh social reality behind the façade. Instead of banning the ornaments, as in the modernist tradition, the project proposed to use them as symbols that represent the community. The drawings are based on a selection of the last remaining ornaments found in Wedding, Berlin.

In recent decades, we have seen a revival of ornamentation as many landlords seek to reconstruct the original look, driven by similar financial motives as their predecessors. Today, an old building is associated with luxury and authenticity, and people are willing to pay a high price, driving up rents and contributing to an unequal distribution of different income groups. While rents are rising steadily, people have to move away or end up on the street. Leopoldplatz clearly shows this trend. Residents complain about drug-related crime and burglaries, with homeless people and drug users seen as the main culprits. There are several political initiatives that aim to change the situation, like the artist in residency program itself, which was made possible through resources from the Berliner security summit. The project’s focus was to warn for possible negative consequences of this transformation. Is art being instrumentalized in similar manner as the 19th century decorations, as a mere decorative layer (Schöne Schein), obscuring the underlying social problems?

By reintroducing the decorations that once symbolised the luxury and security of a home into the public space, the work tried to evoke responses from both residents and the homeless on notions of public space, (social) housing, inclusivity and safety. During the drawing sessions passersby shared their stories and thoughts about Leopoldplatz. These encounters were written down in a logbook and used for a publication that was distributed in the neighbourhood by the end of the project. The premises of the project is that when the multitude of the community can be heard, they become guardian spirits themselves. It’s by amplifying the harsh social reality that fundamental negative influences (real estate speculation, gentrification, etc.) can be warded off, in similar manner as the protective function of the apotropaic ornament. Instead of hiding or excluding the unhoused and the drug users, the social problems at the square can be used as a strategy to offer protection against larger, more fundamental problems, such as profit-driven developers who look for ‘safe’ places for their investments.

*All donations, received during the project were donated to Fixpunkt, an organization that stands for the development and implementation of innovative ideas in health promotion and crime prevention as well as daily structure, employment and qualification for illegal drug users in Berlin.